Who knows? X D ? theres no parrot here anymore at least the grey one, cant say the same with the red one : V

Just add a Dannish or Finnish Soumi instead of Swedish, its not that deep.

Most pointless argument ever.

Yes.

Finns kp31 is just kp31. Not kpist37.

“There were no smg’s to give for only combat unit sweden had.”

While just little bit earlier you said finns provided swedes with smgs.

Finns had four thousand ( 4000 ) kp31’s when winterwar began and by the time when there was any significant amount of swedish volunteers they were assigned to rather silent front up in the north so finns could be sent to karelia where the massive invasion was going on.

Finns were fighting worlds largest army of that time and you think finns could spare smg’s to 2nd line auxiliary volunteers.

Good thinking.

Im sure there was much more dire need in stockholm for those kpist37’s.

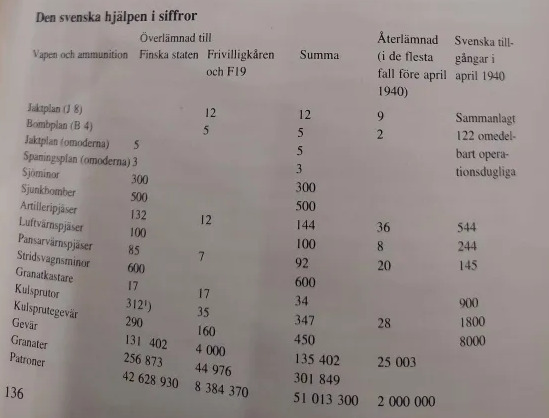

Original (page 136):

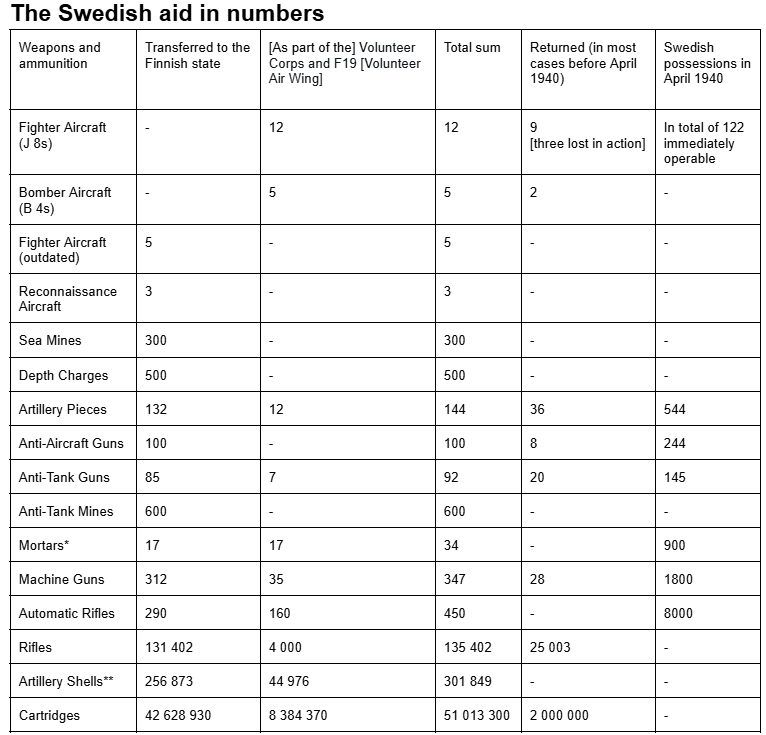

Translation by me:

Translator's Notes:

*The technically correct translation would be “Grenade Launchers,” though with context I will assume it’s supposed to be Mortars. The Swedish language is naturally less precise than the English language (just look at all the various words for an unpowered wheeled vehicle, e.g., “wagon,” “chariot,” “stagecoach,” “trailer,” etc.; it’s all just “vagn” in Swedish).

**In Swedish terminology, “Granater” can refer to several different things in Swedish, either handheld grenades, mortar shells, or artillery shells. Considering the sheer quantity of these that were given, I find it unlikely that this is referring to handheld grenades; artillery shells make more sense, and I assume they’re a combination of all types of artillery (AA and AT included), though I do not leave out the possibility that mortar shells are also included in the total number.

@TUSUPOLISI69 Would you be so kind as to tell me what’s not on the table of contents…?

Source: C-A Wengel (ed.). Sveriges Militära Beredskap 1939-1945 [Sweden’s military preparedness 1939-1945]. Stockholm: Militärhistoriska avdelningen vid Militärhögskolan [The Military History Department of the Military College of Sweden], Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1982.

Militärhögskolan has since the publishing of this book been reorganized into the “Försvarshögskolan” (officially called the “Swedish Defence University” in English).

Now this is how you reference stuff.

Finland recieved no SMGs from Sweden, any guns using the 50-round magazine would have to be the domestic Finnish Suomi, not non-existant imports of the Swedish version.

Please edit your suggestion accordingly. @Декард

With that out of the way, here are some interesting excerpts from the book (with, again, translations from me):

Translator’s Note:

The book is written in old-school Swedish officers’ language, very much related to the former “Chancellery Swedish”, the particular refined style of Swedish previously in use by the Swedish government from before the 2000s. If the formulations don’t seem entirely modern, or fluid, that means that I’ve done a good job at accurately translating the text. This is the upper-class, educated, “King’s English” version of the Swedish language.

Glossory:

Wartime readiness period - In Swedish historiography, the ‘wartime readiness period’ (beredskapsperioden) refers specifically to the years 1939-1945, when Sweden, though formally neutral, maintained continuous military mobilization and far-reaching emergency measures in response to the surrounding war. The term has no exact equivalent in English and is used to denote a distinctly Swedish historical experience of prolonged neutrality under conditions of near-war.

Page 133, Author - Tor Lange

“Already in 1928, Finland had reached out for the possibility to, in case of a wartime situation, receive help from Sweden in terms of war material. But when the Second World War broke out, the Swedish-Finnish negotiations within the weapons question had only led to one concrete result of importance: [Finland] had decided that the Finnish artillery calibers would match that of the Swedish. Furthermore, the field artillery that already existed would be provided with new barrels, in which they would be able to utilize the same types of ammunition [as the Swedish defence industry].”

In other words, the only standardization between Swedish and Finnish forces was with their artillery complements. No standardization in terms of small arms; the only source for 6.5 Swedish or 9x20 Browning Long ammo would be through Sweden, as Finland lacked both domestic need, supply, and production of said ammo types.

This explains the enormous quantity of rifle ammunition given as well, as it would have been critical to make sure that the corresponding small arms aren’t useless in service. With all MGs, ARs, and rifles included, that’d still leave nearly 200 rounds of ammunition for each weapon.

Page 133, Author - Tor Lange

“With the outbreak of the war in September of 1939 [led to the decision] that export-designated [war] materials could be seized for ourselves, so that at least we could fulfill our training needs. But the delivery capacity was low under the first winter, and the war industry had yet picked up speed. Probing internationally revealed that it would have been significantly much harder to purchase war material [from foreign sources]. A Swedish delegation was sent, for example, in the middle of December 1939 to Berlin with a wishlist of materials for 500 mil [Swedish Crowns]. However, the forecast to whereby get anything was and remained too small, [amongst other things] because the delivery of German aircraft to Sweden could worsen the relationship between Germany and the Soviet Union, which was based on the non-aggression pact of August 1939. [The Germans] could not remain blind to the suspicion that a part of the orders could be diverted for Finland.”

- Despite appropriating war materials meant for exports, supply remained critically low in Sweden, and it was assumed that the extra materials gained from this would barely cover the needs to at least train up an expanded military (even if it wasn’t then enough to supply that newly expanded military).

- The Swedish defence industry was unable to cope with demands, because it had yet to fully transition to a wartime economy even after the first winter of the war.

- Buying from foreign sources was impractical, as the most practical source (Germany) did not want to upset the Soviets.

Page 133-134, Author - Tor Lange

![]()

" The transition of our country to an improved war organization, to begin with was slated to take into effect in January of 1940, put forth new demands, not least of all on the [question of weapons]. One was forced to bargain on the demands which led to – as it’s called in high command orders – “certain material exceptions.” Thus the amount of artillery divisions [became] three instead of [the normal] four, because the amount of artillery pieces did not allow for any more. […] The garrison-infantry regiments of I 2 and I 11 were disbanded, and from the saved equipment they were put at Finland’s disposal."

- Sweden had to skim the books to make sure that the resources they had could be stretched to accommodate rearmament and Finnish aid demands, going so far as to reduce the standard division complement of artillery by a 4th within.

- Much of the aid to Finland came from surplussing of gear originally used by garrison formations. Not exactly the crack divisions of the Swedish Army (and thus unlikely to possess the brand new weapons systems recently acquired by the military, such as SMGs).

Page 134, Author - Tor Lange

“The Landstorm’s weapons equipment was weak. There was a [lesser shortage] of artillery and air defence pieces; otherwise, there was very little heavy weaponry, and there was also a question of scarcity of the ammunition for the little that there was. The average Landstorm soldier was on average going to have to be content with carrying the same rifle in hand that his predecessor had 25 years earlier. There was also a question of acquiring weapons for the Home Guard, , which naturally didn’t exist until May of 1940 but which had, since several months earlier, begun to take shape. By and large, you could say that it wasn’t the relief efforts for Finland which was the deciding factor in which degree the Landstormen or the Home Guard [was equipped].”

Conclusion: The aid that was sent to Finland was not immediately critical, and could not be counted as the foremost reason for the scarcity of gear.

Considering that the Swedes suffered from an immense shortage of SMGs, despite not having sent any as aid to Finland, this does seem to bear out.

Page 134-35, Author - Tor Lange

" Naturally our war material deliveries to Finland meant a bloodletting of our own meagre resources. They could, however, to some extent be replenished in the beginning of 1940. A portion of the transferred materials to Finland was returned before the April-Crisis, but that this would have been possible could of course no one have known during the days of the Winter War. […]. Of the transferred fighter planes to Finland, three were lost in action; the rest were returned immediately upon the end of the Winter War. The older outdated models were never requested for."

“The help to Finland must finally also be seen from a purely economical standpoint: it stretched for a period of a couple of months [Sweden’s] resources to a degree previously unprecedented, which required a redistribution of means, which otherwise could have been used in our own war materials production.”

“Against this backdrop, one can assume that the Prime Minister, in his speech in Malmö on the 24th of March 1940, out of psychological reason added on purpose an exaggeration when he said: ‘[Despite these meaningful material war material deliveries we have still calculated the need for our own war organization have only been delayed on a few points].’”

Once more it is affirmed that the deliveries were significant, but not something that couldn’t be overcome. By the passing of spring in 1940, Sweden had recuperate what it had lost by the manufacture of new gear, and a return of a portion of Finnish aid upon the end of hostilities.

There is also a clear pattern forming here. Old materials are sent to Finland, with the expectation that it won’t be returned, but when the opportunity arises to have some things returned, the requests target only the most modern of gear sent. In other words, what was sent was the things deemed of lesser value, items that were thought to be easier to replenish, with only a portion of the deliveries being worth enough to even bother getting back.

I doubt something as rare, valuable, and difficult to produce as the Kpist m/37s were deemed a part of the non-essential gear that they could afford to send away.

Page 424, Author - Klaus-Richard Böhme

" Not least of all, the difficulties with being able to import war materials drove up the expansion of the Swedish military industry."

“Before the war, Sweden was, thanks to the factories of Husqvarna and [Carl Gustaf’s] by and large self-reliant when it came to small arms. But the large demand for, not least of all, [automatic weaponry] and submachine guns during the first part of the wartime readiness period could not be filled.Bofors was long established, not least of all abroad, as a producer of artillery pieces, although not of heavier kinds. With the outbreak of war, the state could, with the Appropriation Law [of 1939], seize a portion of Bofors production being made for export.”

- Sweden was entirely self-reliant on rifle production.

- Sweden lacked the capacity for the early years of the war to produce automatic weaponry and SMGs at desired levels.

- Bofors, an artillery producer, was a large company of international renown capable of seeing to Sweden’s needs when the export portion of the production was claimed for domestic needs.

Considering that Sweden had been users of machine guns since before WW1, they would have been continually producing and procuring more guns of ever more modern make for a long time; this does explain why they were in a position to send away a portion of the weapons (especially the more vintage examples) to Finland, despite increasing domestic needs.

Contrast this with the sole SMG within Swedish inventory, which was only adopted barely two years earlier, had largely acquired the few examples they had through Finnish manufacture, and had yet to bring the gun into large-scale production inside of Sweden; there is little wonder that these guns were held on to instead.

Page 425, Author - Klaus-Richard Böhme

“One’s own production was dependent upon the assets of raw resources, labour, fuel and energy supply, lubrication, and machinery. By prioritizing, rationing, the use of supplement materials, own extraction, and thanks to some import possibilities, [Sweden] managed to produce at least the majority of the needed war materials. In terms of value, 87% was own production and 13% was imported. Because of the forced mercantilism, the Swedish military industry continually evolved up to 1945 a noteworthy capacity, which should be one of the conditions for a continued Swedish neutral foreign policy even after the war.”

I just thought that this was a good note to end things on.

To be the most accurate of accurate:

- The Kp 31 is the original from Finland, the Kpist m/37 and m/37-39 are just different models of the original meant for Swedish service.

- The 50 round magazine is of Swedish design, but it was also used and produced in Finland to a large extent.

The important thing is that you want the Swedish designed magazine specificly for the Finnish Suomi, not a Swedish one.

Anyway, my concerns have been at least partially met, so I am switching my vote to a yes.