THE ALUMINUM THOMPSON SMG

by SAR Staff

in V17N3 (3rd Quarter 2013), Articles, Articles by Issue, Guns & Parts, Search by Issue, Volume 17

Share on FacebookShare on Twitter

By Frank Iannamico

A Brief History of the Thompson

The Thompson submachine gun was conceived during World War I as a trench broom designed to sweep the enemy from the trenches. Although it was the brain child of John T. Thompson, a retired U.S. Army Ordnance officer, the Thompson submachine gun was designed and engineered by Oscar Payne and Theodore Eickhoff, both employees of Thompson’s Auto-Ordnance Corporation. The company was financed by multi-millionaire Thomas Fortune Ryan, who had made his fortune in the tobacco and transportation industries. After several prototypes were designed and tested the weapon was ready to go into production. The Auto Ordnance Company had no facilities for large scale manufacturing, so the project was farmed out to Colts’ Patent Fire Arms Company in Hartford Connecticut. A total of 15,000 Thompsons were produced during 1921-22. Since World War I had ended a few years earlier there was not much of a market for the submachine guns. The Company sold a small number to a few law enforcement agencies and large corporations.

Right side of the aluminum Thompson. Note the receiver has Auto-Ordnanceís New York address on the side, confirming that the receiver was made during the early stages of production.

Unfortunately, gangsters of the era discovered the Thompson and the weapon became infamous in that role. To further tarnish the weapons image, the use of the Thompson by criminals was greatly exaggerated in the popular gangster films of the day. The submachine gun’s criminal use, both real and imagined, resulted in new laws being enacted in 1934 to keep the weapons out of the hands of criminals that included a hefty tax on each weapon. Commercial sales of the Thompson all but ended. The remaining inventory of Colt Thompsons and much of the tooling used to manufacture them was placed in storage. The Auto-Ordnance Corporation was deep in debt to the heirs of Thomas Fortune Ryan, who had passed away in 1928, and they desperately wanted to sell off the remnants of the failed business.

Bottom view of the aluminum receiver. Note the black anodizing on the inside surfaces of the receiver. The anodizing was needed to keep the steel bolt from sticking to the inside of the aluminum receiver. (Courtesy of the National Firearms Centre, Leeds, UK. Photographed by Robert G. Segel)

Enter J. Russell Maguire

On 1 September 1939 Germany invaded Poland, a few days later both England and France declared war on Germany; it was the beginning of what would become World War II. Neither France nor England was prepared to fight a major war.

J. Russell Maguire was an American industrialist and opportunist. Well aware of the situation unfolding in Europe, he surmised there would be a huge market for war material especially weapons. Maguire learned of the Auto-Ordnance company and after considerable negotiation, a deal was finally struck giving Maguire controlling interest in the company.

The remaining Thompsons that were made by Colt in the 1920s were quickly sold with France and England among the first customers. As the fighting in Europe increased, Maguire needed more Thompsons and approached the Savage Arms Company to see if they would be interested in manufacturing the guns. Ironically, Savage had bid on the original 1920 contract, but were underbid and lost the contract to Colt. The first contract with Savage was signed in December of 1939 for 10,000 Model of 1928 Thompsons using much of the same tooling that had been used by Colt over eighteen years earlier. Savage manufactured the Thompsons in their Utica, New York plant. The Thompsons first had Auto Ordnance’s New York address, and later their Bridgeport, Connecticut address on the receivers. The only markings that indicated Savage was the manufacturer was a letter S prefix on the serial number.

The aluminum Thompson 1928 Model made by Savage. The project was undertaken and financed solely by Savage Arms. (Courtesy of the National Firearms Centre, Leeds, UK. Photographed by Robert G. Segel)

Soon the U.S. military’s demand for the Thompson became such that Auto-Ordnance opened a second plant in Bridgeport Connecticut in 1941. Initially, the new plant only manufactured receivers and trigger frames. Many of the components to complete the weapons came from Savage and other subcontractors. The 1928 Thompsons produced at the Auto-Ordnance plant had a Bridgeport, Connecticut address on their receivers and the letters A.O. preceding their serial numbers.

The Thompson was originally designed during an era when firearms were made to a very high standard and built to last. Fit and finish was paramount and only high quality metal and wood was used in their construction. However, since the outbreak of war huge quantities of weapons were needed. New weapons were being designed using stamped sheet metal to replace the old world method of machined receivers and parts. This new method allowed for faster production and less cost; appearance was no longer a priority. By the time World War II began in Europe the original design of the Thompson was nearly twenty years old. However, it was the only submachine gun available to the Allies.

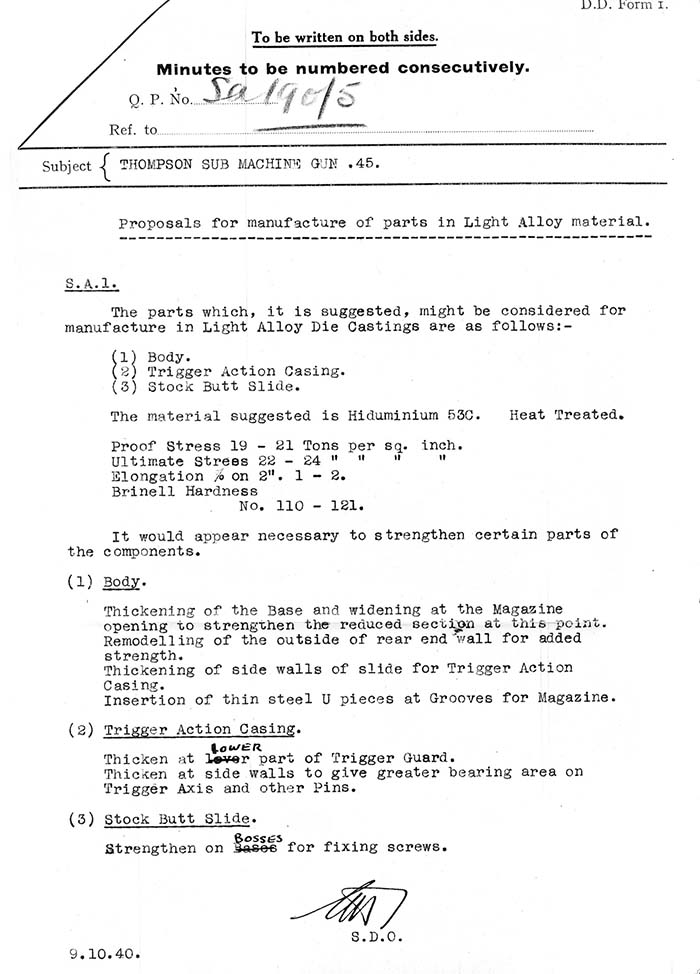

A September 1940 dated document from the Springfield Armory with some proposals and specifications for making Thompson parts from aluminum. (Courtesy of the Royal Armouries Library, Leeds, UK)

The 1928 Thompson was time consuming to manufacture, expensive and heavy. From the time the 1928 Model was placed back into production, ways to reduce its cost and labor time were sought. The Auto-Ordnance Corporation had a difficult time keeping up with the ever-increasing demand for the Thompson. To increase production they had to either procure more machine tools, and increase the work force or simplify the parts, where possible, for easier manufacture. There were still a few amenities on the 1928 Thompson that could be eliminated in order to expedite the weapon’s production. After the complex Lyman rear sight, the next elaborate feature of the Thompson to be eliminated for the sake of faster production was the finned barrel. Also eliminated was the checkering on the actuator knob and control levers.

One of the most difficult tasks in manufacturing the 1928 receiver was machining the surfaces on the inside of the receiver where the Blish lock rode. Savage engineers discovered that the Blish lock used in the 1928 Model was of dubious value and designed the M1 Model, without it. The M1 Thompson submachine gun was a simplified version of the Thompson, with a new receiver and trigger frame, but using many of the 1928 Model’s internal parts. The M1 design eliminated many features of the 1928 that made the weapon labor intensive, and expensive. The new M1 was much better suited for a military application. The M1A1 Model was introduced just a few months later to further simplify the basic design by eliminating: the firing pin, the firing pin spring, the hammer, the hammer pin and simplifying the bolt with a protrusion on the bolt face that served as the firing pin.

The trigger frame was also made of aluminum. Note the early style milled and checkered safety and mode of fire selector levers. (Courtesy of the National Firearms Centre, Leeds, UK. Photographed by Robert G. Segel)

The Aluminum Thompson

One of the disadvantages of the 1928 Thompson was its weight, another was the time required to manufacture the weapon. There had been a number of advancements in metallurgy during the period especially with aluminum in the aircraft industry. During 1940, Savage Arms decided to produce a number of prototype Thompson receivers and trigger frames from heat treated aluminum forgings. The material was lighter and could be machined much faster than steel.

The Aluminum prototypes were made in Savage Arms’ model shop. The project was undertaken and funded strictly by Savage. The aluminum Thompsons were fitted with handguards, pistols grips and buttstocks made of Tenite, a cellulosic thermoplastic manufactured by the Eastman Chemical Company. The plastic material was thought to be more durable, cheaper and lighter than walnut, which was becoming scarce because of the war. However it was discovered that Tenite did not hold up well when subjected to high temperatures; it became slippery when wet and very cold to the touch during winter conditions.

The markings on the aluminum receivers were the same as those on steel production guns. The letter S preceding the serial number signifies the receiver was manufactured by Savage Arms. The flat-milled ejector, knurled actuator knob and control levers signify early production. (Courtesy of the National Firearms Centre, Leeds, UK. Photographed by Robert G. Segel)

Most all of the internal components and the barrel were standard military production items. Most of the receivers had the Savage S prefix, but were not serial numbered. All of the known aluminum Thompsons have no type of finish. If the project had been successful they probably would have been anodized or painted black.

Savage engineers encountered several problems with the aluminum receivers. One was the hard steel bolt was gaulding to the softer aluminum receiver. This problem was solved by anodizing the inside of the receiver where the bolt rode. However the anodizing could not hold up to the 20,000 round testing. Another problem was the stretching, and eventually cracking, of the rear of the receiver. Efforts to design a suitable buffer to prevent the problem were unsuccessful.

All the internal components of the trigger frame were standard steel parts, the same as those used in production Thompsons. Note the checkered Tenite plastic pistol grip. (Courtesy of the National Firearms Centre, Leeds, UK. Photographed by Robert G. Segel)

The aluminum prototypes Thompsons were eventually sold to the Auto-Ordnance Corporation, who made the decision not to submit them to the U.S. Ordnance Department for consideration. Reportedly, there were forty aluminum receivers and trigger frames manufactured. According to Savage, all of the aluminum Thompsons were to be destroyed; quite apparently they were not as there are several examples known to still exist.

On 25 April 1942, the M1928A1 Thompson was reclassified as “Limited Standard.” The M1928A1 weapons were to be replaced in service by the new M1 version of the Thompson and the stamped sheet metal M3 submachine gun that was under development by the Ordnance Department and the Guide Lamp Division of General Motors. Due to unforeseen problems, the M1928A1 model continued to be manufactured until the autumn of 1942.

The official end of the M1928A1 model came at an Ordnance Committee meeting held on 16 March 1944 item 23248; Memorandum for the Standards and Specification Section, Conservation Branch, Production Division, Army Service Forces. It was noted for the record that, “U.S. Army specification 52-3-30 of Gun, Submachine, Thompson, Caliber .45 M1928A1 be canceled in accordance with paragraph 30, AR 850-25.” The request was approved.

The Tenite plastic foregrip on this aluminum Thompson appears to have warped after being exposed to heat from the barrel during firing. Tenite was known to not hold up well when exposed to high temperatures. (Courtesy of the National Firearms Centre, Leeds, UK. Photographed by Robert G. Segel)

A standard World War II era U.S. Model of 1928A1 Thompson submachine gun made by the Savage Arms Company in Utica, New York. Note the Auto-Ordnance Bridgeport, Connecticut address on the receiver.

The M1 Thompson. The 1928 Model of the Thompson was simplified by the engineers at Savage Arms and the resulting weapon was the M1 and later the M1A1 Thompson. One of the major changes was the elimination of the ìBlish Lockî used in both the Colt Thompsons and World War II era 1928 models.

*This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V17N3 (September 2013)*Y