An Alternative Layout

SPG designs hit a dead end in many nations by the end of WWII. The concept of a heavier gun on the same chassis stopped working. Regular guns were getting so large that there were issues with the chassis. The results were essentially the same as just putting the gun in a tank with a rotating turret. This was especially true for medium SPGs. Germany, the USSR, and Great Britain eventually ended up with medium tanks that had the same gun as medium SPGs. Several nations (especially Germany and the USSR) ended up overloading the front suspension. This led to a search for new solutions. This led to the Uralmash-1, the most unusual Soviet late war SPG.

In search of a future-proof layout

The SU-100 SPG was accepted into service with the Red Army on July 3rd, 1944. In addition to a more powerful 100 mm D-10S gun, this vehicle received 75 mm of front armour and a commander’s cupola. It became clear that the limit of the chassis was reached. The SU-100 weighed 2 tons more than the SU-85, all of which weighed heavily on the front of the vehicle. Complaints of broken wheels and suspension springs began coming in starting with late 1944. This was not the only issue. The SU-85’s gun had an overhang of under 2 meters, but the SU-100’s gun stuck out by 3350 mm. This resulted in additional issues in combat. Risk of damaging the gun when driving on bumpy terrain, in forests, and in cities increased. Furthermore, the front suspension springs began to sag. This was noticed even on the prototype.

A draft of the SU-100M1, a potential replacement for the SU-100, dated October 7th, 1944.

This was not news to the UZTM design bureau. Work on the SU-D25, a SU-85 with a commander’s cupola and the 122 mm D-25S gun, began in the fall of 1943. The gun’s overhang was 3300 mm and the mass rose to 32 tons. The SU-D25 project evolved into another vehicle, the SU-100P. The issues of heavy load on the front wheels and significant gun overhang were obvious and noted even earlier during work on experimental SPGs on the ISU-152 chassis. The first solutions of these issues also had to do with the heavy SPGs. In late March of 1944 factory #100’s design bureau presented a deeply modernized IS-2 tank with a rear fighting compartment designed under the direction of N.F. Shashmurin. According to the drafts, an SPG with a rear fighting compartment was planned on the same chassis. The work did not proceed for various reasons, and so the ball was in UZTM’s court.

The driver’s compartment was separated from the fighting compartment. Unlike in later projects, the SU-100M1 did not have a passageway connecting the two.

A rear fighting compartment was not a new thing for Soviet SPGs. This layout was first suggested for the A-46 medium tank destroyer back in 1941. It had obvious advantages and disadvantages. One advantage was that the gun overhang was either minimized or disappeared entirely. In case of open or semi-enclosed fighting compartments, it was also much easier to serve additional ammunition during firing.

There were also many disadvantages. The driver’s compartment would be cramped, the engine compartment would have to be more compact, and the dense layout would introduce issues with access to the engine and cooling system. The biggest issue was that a redesign of the chassis would be required. Few tank building nations could allow this during a war. The USSR considered altering the chassis undesirable, as it would require more time to set up production. The SU-76M with its rear fighting compartment is an exception, but it was a necessary evil. The T-70B chassis in its initial form was unsuitable for building an SPG.

The transmission remained in the rear, which resulted in a height increase of 100 mm compared to the SU-100.

Another interesting point is that several nations began to search for a new layout at the same time. This was especially true for Germany. It was clear that the reserves of light and medium chassis were exhausted. The maximum acceptable load on the road wheels was reached and then surpassed, with obvious results. Given that there was already a successful experience with the Panzerjager Tiger(P), Krupp proposed a series of light and medium tank destroyers with a rear fighting compartment in October-November of 1944. The 6th Department of the Ordnance Directorate rejected them all, chiefly due to excess mass. Nevertheless, it’s interesting that designers in different nations had the same ideas.

ESU-100, a variant with an electromechanical transmission.

It is not known when exactly the UZTM design bureau began working on alternative variants of the SU-100. One can confidently say that investigation into the vehicles was already mentioned in the plan for experimental work for the second half of 1944. The document, dated August 22nd, 1944, describes “an SPG on the T-34 and T-44 chassis with a D-10S or D-25 gun and rear fighting compartment”. 100,000 rubles were allocated for the design and blueprints. The due date was Q3-Q4 1944. In case of the T-34 chassis, two vehicles were added to the prospective SU-122P: the SU-100M1 and ESU-100. They were similar in terms of armament, hull layout, and overall concept.

The electromechanical transmission was not just larger, but also heavier. Installing it required a new layout for the driver’s compartment and engine compartment.

The vehicle was only 40 mm longer than the SU-100, but the height of the casemate increased by 100 mm to 2300 mm. This was necessary due to a decreased fighting compartment height in the new layout. While the engine and cooling system moved to the middle of the hull, the gearbox and other transmission elements remained where they were. This required adding a driveshaft leading to the gearbox. A large access panel was installed in the rear of the vehicle to work on the gearbox. This was not a new problem, the experimental GAZ-71 SPG also had a similar layout. Even though the fighting compartment was smaller, the ammunition capacity was greater: 39 100 mm rounds. The mass increased by a ton compared to the SU-100, reaching 32.6 tons. This was not only due to the layout, as the front armour was thickened to 90 mm. The top speed was estimated at 47.5 kph.

The driver had to be shifted to the left.

The driver’s compartment was also altered. Like on the Ferdinand, there was no access to it from the fighting compartment. A lack of space also meant that the fuel tanks were next to the driver. Like on the SU-100, the driver’s hatch was placed in the upper front plate.

SU-100M2, an alternative on the T-44A chassis.

The ESU-100 was similar to the SU-100M1, but it was even heavier: 35 tons. The ESU-100 used an electromechanical transmission developed at factory #627. The transmission was a product of EKV an IS-6 tank (Object 253) development. The transmission was not just heavier, but also bigger, leading to a decrease in ammunition capacity to 35 rounds. Changes were also introduced in the engine compartment. The GT-627 generator forced the designers to shift the engine forward, partially entering the driver’s compartment. The driver was moved to the left, as were the fuel tanks. Due to increased mass, the top speed dropped to 42 kph.

The lighter and lower chassis made the SU-100M2 preferable to the SU-100M1.

As mentioned above, the T-34 was not the only prospective chassis for the SU-100’s replacement. GKO decree #6209s “On organizing T-44 tank production at factories #75 and #264” was signed on July 18th, 1944. The T-44A (an improved variant of the tank) entered trials on August 18th, and on September 23rd NKTP order #573s listed a number of corrections that would have to be made before the tank entered production. It was clear that mass production was around the corner, and designing the SU-100M2 SPG was a logical step.

Sloping of the front hull allowed for a decrease in mass.

The layout of the hull was largely similar to the SU-100M1, and so was the ammunition capacity. However, the new chassis allowed the height to decrease to 2200 mm, the same as the SU-100. The mass was also the same as the SU-100: 31.6 tons. Like on the SU-100M1, the driver sat in the center of his compartment. The slope of the sides was even steeper. The driver’s hatch vanished from the front of the hull and moved to the roof. The thickness of the armour was also increased: the upper and lower front hull were 90 mm thick and the sides were up to 75 mm thick. The speed was estimated to be the same as for the SU-100M1, but the fuel capacity decreased from 560L to 450 L. The tank used a more powerful V-2-44 engine that consumed more fuel.

SU-122-44, an alternative vehicle with a front fighting compartment. This vehicle had highest priority at one point.

The SU-122-44 was the last of the alternatives. This vehicle was a counterpart to the SU-100P. It was developed using the classical layout with a front fighting compartment. This design was a backup plan in case the rear fighting compartment idea did not pan out. One advantage of the SU-122-44 was that it did not require as many changes to the T-44A chassis. However, the barrel overhang was 3070 mm, while it was no more than a meter on its competitors. Thanks to a different layout, thicker armour, and the more powerful D-25T gun, the mass of the SU-122-44 reached 32.8 tons. However, a comparison with the SU-122P shows that the increase was worth it. The SU-122-44 was the roomiest, which not only improved the crew’s working conditions, but also allowed the increase of ammunition capacity to 40 rounds, a third more than the ISU-122. The vehicle also had superior armour, as its 90 mm upper front plate was positioned at an angle of 60 degrees. Based on the performance of the IS-2, this armour protected from the 88 mm Pak 43 gun at a range of 500 meters. The crew of four was an issue. Practice showed that the A-19 and D-25 needed two loaders, otherwise the average rate of fire was 2.5-2.75 RPM. This was confirmed in trials of the SU-122P.

There can be only one

The UZTM design bureau finalized all projects on October 7th, 1944. In all cases the overall direction was given by L.I. Gorlitskiy and the lead engineer was N.V. Kurin. Documentation on all five vehicles including the SU-122P was sent to the NKTP in mid-October. By that point the SU-122P was already built and undergoing factory trials. Trials showed that the average speed of the SU-122P was lower than the SU-100. It was becoming more and more clear that the T-34’s chassis was reaching its limits.

Initial layout of the SU-101 prepared by early March of 1945. The prototype followed these blueprints.

The NTKP’s decision regarding the UZTM’s projects was reasonable given this information. The T-34 chassis was no longer satisfactory, and so the SU-100M1 and ESU-100 were left behind. On October 26th, 1944, Malyshev signed NKTP order #625s choosing the projects on the T-44A chassis. UZTM’s design bureau had to complete documentation for the SU-122-44 and SU-100M2 by December 25th. The SU-122-44 split into two vehicles: the SU44-100 and SU44-122. A variant with the 100 mm D-10S gun would be developed in addition to the one with a D-25S. The chassis was also going to change, in part due to thicker armour. The front armour grew to 120 mm and the sides to 75 mm. This protected the tank from the 88 mm Pak 43 L/71 at any range. Most attention was paid to improving the SU-122-44, presumably the NTKP considered this vehicle the most promising.

The layout changed significantly compared to the SU-100M2, and the armour was radically improved.

Despite high interest in the SU-122-44, the SU-100M2 had its share of required changes. A reworked project was due by January 1st, 1945, where the engine was shifted to the right and the driver was shifted to the left to allow him a passage into the fighting compartment like on the SU-76M. A hatch was placed above the driver like on the T-44 to allow him to drive while sticking out of the hatch. A DShK AA machine gun was installed on the commander’s cupola. A fume extractor was going to be installed on the gun and MDSh smoke bombs were to be carried on the rear. The list of improvements numbered 11 in all.

The sides were sloped at 45 degrees to make them stronger.

The optimism regarding the SU-122-44 was short lived. Calculations for improved armour made in December of 1944 proved that the vehicle was a dead end. The mass of the vehicle grew, but the T-44 showed issues with peeling road wheel tires as is. Trials of the SU-122P also played a part. The T-44, which was supposed to be used without much modifications, was in question too. Factory #75 had difficulty getting production off the ground, and the blueprints sent by factory #183 were already changed. The UZTM was in danger of getting involved with a lengthy battle in mastering production themselves. In short, there was no longer any sense in producing the SU-122-44.

The SU-102. Initially it only had different armament from the SU-101, but in practice the prototype had many internal changes.

UZTM director B.G. Muzrukov declined to work on the SU44-122 and SU44-100, focusing instead on the SU-100M2. Muzrukov informed Malyshev of this decision, who responded with understanding. The GBTU’s SPG branch did not entertain the idea of a “classical” SPG on the T-44 chassis from the very beginning. The 3rd Department of the SPG branch lists “control over the development of an SPG with a rear fighting compartment” as work for the fall-winter of 1944. The SU-122-44 is absent from these plans. A special commission from the NKTP led by I.S. Ber arrived in January of 1945 to review the new blueprints. The commission agreed with the UZTM’s findings. The variant with a rear fighting compartment was more promising. Calculations showed that thicker armour will result in a small increase in mass. Furthermore, the fighting compartment could fit not only the 100 mm D-10S, but the larger 122 mm D-25S. The commission pointed out a series of issues that would have to be corrected before the final project was submitted.

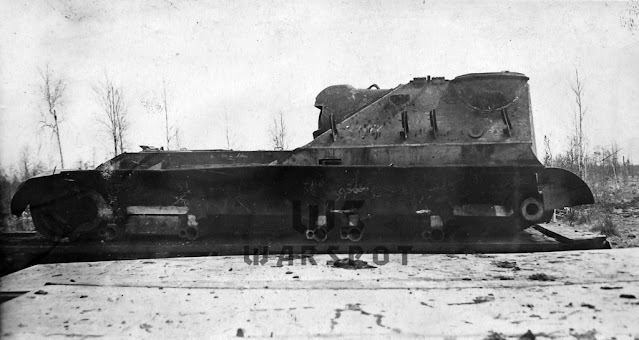

SU-101 hull prepared for testing.

The final version of the SU-100M2 was presented in March of 1945. The mass increased to 32.4 tons due to improvements and changes to the armour. The NKTP approved this submission with NKTP decree #107s signed on March 7th, 1945, which also gave the vehicle the name “Uralmash-1”. According to the order, the prototype armed with the 100 mm D-10S gun was due on May 1st. It was named SU-101. A second prototype with the 122 mm D-25S gun was due on May 15th. This vehicle was named SU-102. An Uralmash-1 hull was also expected for penetration trials. Some final changes were introduced before production. The cooling system and fighting compartment ventilation system would be altered, the engine compartment was insulated, the ammunition capacity was increased to 40 rounds, the suspension was reinforced, and protection of the gun and lower front plate was improved.