The Thompson Autorifle, (also referred to as the Thomoson Model 1923 Autoloading Rifle; and the .30-06 Model 1923 Semi-Automatic Rifle, among others, etc.) was a semi-automatic rifle that used a Blish Lock to delay the action of the weapon. It was chambered in .30-06, with the 1923 model in 7.62×54mmR Russian rifle rounds.

Several prototypes of the Autorifle were submitted by Auto-Ordnance to the military for the semi-automatic rifle trials, but it was not adopted. The Autorifle Model 1929, in .276 Pedersen, was tested in a competition with the rifles by J.D. Pedersen (delayed blowback) and John C. Garand (gas-operated), which culminated in the adoption of the M1 Garand.

On the positive side, the Autorifle action avoided the complexity of recoil-operated and gas-operated actions. On the negative side, the Autorifle required lubricated ammunition for proper functioning and the ejection of spent cartridge casings was so violent as to be hazardous to bystanders.[1]

Function

[edit]

For reloading, the Thompson Autorifle uses an interrupted screw delayed blowback operation where the bolt has 85° angled interrupted rear locking lugs that have to overcome a rotation of 110° ( 90° to unlock before the angle blend of 70°/40° and 6°) that delays the action until the gas pressure drops to a safe level to eject. The bolt cocks the striker on opening (a la Mauser) and fires from a closed position. When firing, the trigger when pulled pushes a lever connected to a sear to fire the weapon. The receiver is of a round section with the safety switch at the rear along with the rear sight. The magazine is stripper fed holding 5 rounds and lubricated by oiled pads; later prototypes used 20-round M1918 BAR magazines.[2]

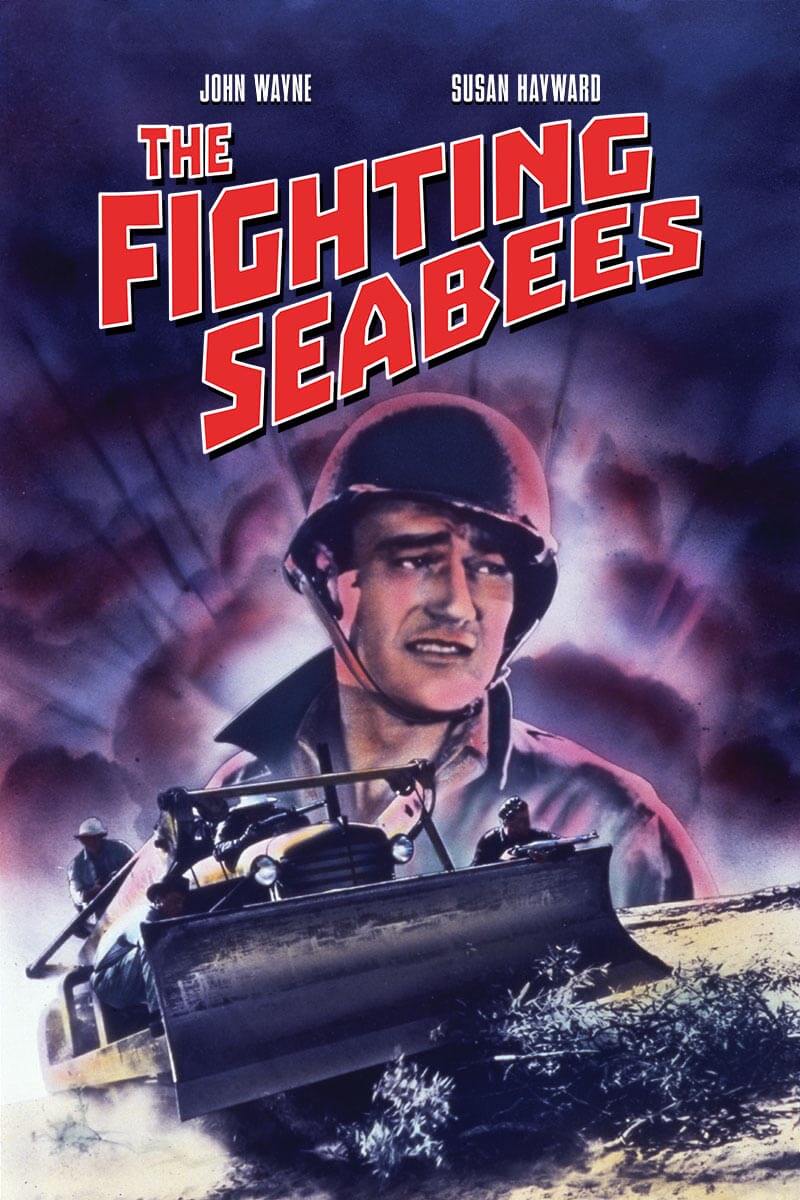

I love the John Wayne movie it would be great to see support classes in more games and movies. Engineers and medics need more love than they get sadly assaulters and machine gunners get all the love.

A great way to add some color to the game, enlisted is great when it is a what if as long as no time traveling ak-47’s. Seeing non-combat support units could mean more variety in complexation.

1. “Seabees” Is a Play on Words.

The Seabees’ name isn’t actually “Seabees.” The unit’s official name is United States Naval Construction Battalions, or CB, for short. It’s much easier to say “CB” or “Seabee” than “United States Naval Construction Battalions,” or even “construction battalions.”

A name like Seabees also lends itself to the easy creation of morale patches and insignia, which are all the rage in the military, if you haven’t noticed.

2. The Original Mascot Was a Beaver.

This makes sense when you think about it. The beaver is an industrious mammal, at home in both the water and on land. Frank Iafrate, designer of the original logo, was instructed to create one using a Disney-type character, according to the U.S. Navy Seabee Museum. Iafrate then discovered the beaver runs away when threatened. That’s not a good mascot for the U.S. Navy, especially during World War II.

Advertisement

“Then I thought of a bee. … The busy worker, who doesn’t bother you unless you bother him. But provoked, the bee stings. It seemed like an ideal symbol,” Iafrate told CNN in 2015.

(National World War II Museum)

3. The Navy Needed Fighting Construction Workers.

Even in the days of World War II, the U.S. military had no problem contracting out construction projects to third parties. Unfortunately, civilian construction workers building critical infrastructure aren’t allowed to fight back when attacked. Under international law, they could be considered guerrilla fighters and might be executed when captured.

A construction crew that also happens to be a military unit, however, would make a pretty big surprise for any enemy against which they thought they were about to get an easy win on any given day. Attacking Japanese troops would learn quickly they were fighting construction workers trained by the Marine Corps.

Hence their other motto, “We build, we fight.”

4. Seabees Were the Oldest and Highest-Paid Sailors in WWII.

In recruiting the first Seabees, the Navy was looking for the same seasoned skilled tradesmen found on any major construction site in America. They had to be talented and fast, even if they were a little bit older than other recruits. As a result, they received higher rank upon entering the Navy than most other recruits, too.

In order to fill the Seabees’ ranks with these skilled workers, physical standards and age limits were waived for any recruit under age 50. Some 60-year-olds still managed to slip through, so the mean age for a Seabee during the war was 37, when the average age for the rest of the military was just 26.

5. A Seabee Unit Could Do Almost Anything.

With just more than 1,100 skilled men and officers, a Navy construction battalion could be deployed and build almost anything. It was made up of four companies of construction workers and deployed alongside medical, dental and logistics personnel, along with all the other kinds of professions a unit needs in the field.

As construction projects became bigger and more complex, multiple CB units were deployed to the same projects. By the end of the war, the Navy had more than 258,000 men working in the Seabees, well short of the number it needed.

6. Black Seabees Filled in for Fallen Marines at Peleliu.

The need for cargo handlers increased throughout the war, Black men were drafted to fill those ranks in segregated units. The 17th Special CB unit was attached to the 1st Marine Pioneers the day they landed on Peleliu (pronounced peh-luh-loo). As Japanese resistance stiffened, the 17th CB began hauling ammunition to the front and carrying the wounded to the rear.

As the fighting on Peleliu ground on, more and more Marines were falling to enemy fire. For three days, the Black sailors of the 17th Special Construction Battalion filled in for those who were killed or wounded by the enemy.

During World War II, the 17th Special Seabees, attached to the 7th Marine Regiment, rest amid the rubble on the island of Peleliu, Sept. 1944. (National Archives)

7. The Original Seabees Built Projects in Every Theater.

Seabees were paving the way to victory for the Allies every step of the way. They built more than 400 projects at a cost of $11 billion in the Caribbean, North Africa, Sicily, Italy, England, France, Canada, Greenland, Iceland, China, Alaska, the Philippines and most of the islands in between.

An estimated 300 Seabees were killed in action, and another 500 were killed in construction accidents. The Navy’s go-to construction crews also earned five Navy Crosses, 33 Silver Stars and 2,000 Purple Hearts.