British submachine gun trials, 1915 - 1939

It is often said of the British Army that before World War II, they completely disregarded submachine guns (or “machine carbines” as they were then known) purely on the basis that they were “gangster weapons”. This is only half-true - while the pre-WWII British Army was decidedly more conservative than most militaries of the time when it came to small arms, there were some steps taken to investigate submachine guns.

The first submachine gun to be tested by the British Army was the progenitor of the entire concept - the Italian Villar Perosa, demonstrated at Hythe on the 7th of October 1915. The weapon had been brought to England by an Italian representative, Mr. Bernachi, who submitted it to the Small Arms Committee. A further test took place at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield on the 18th. The report from the SAC described the weapon as “very suitable for trench work”, but there was no interest from the General Headquarters in France.

The Villar Perosa submachine gun demonstrated for the SAC. This model was a one-of-a-kind piece chambered in .455 Webley.

During the closing stages of the war, in September 1918, a captured German Bergmann MP18 (serial no. 214) was tested by the SAC, who sent a report to the General Headquarters. The GHQ took a very dim view of the MP18, who seemed to be under the impression that the Germans were planning to use the weapon as a substitute for rifles. For the GHQ, the MP18′s failing was its pistol-calibre ammunition, which they felt was far too underpowered - their concern was that use of low-power bullets would encourage the Germans to issue body armor, which the MP18 would be incapable of penetrating. The GHQ’s response to the SAC essentially dismissed the MP18 as a novelty and insisted that British infantrymen continue to be issued full-power rifles and machine guns.

Despite now being considered a revolutionary weapon, the contemporary British view of the MP18 was that it was little more than a novelty.

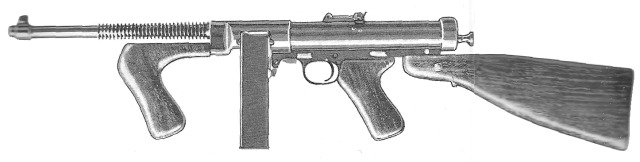

After the war ended, various new submachine gun designs did begin to emerge, although not all were based on the MP18. Brigadier General John Taliaferro Thompson’s now-famous “Tommy gun” was one such weapon, which he had conceived during the war as a weapon to break the stalemate of trench warfare. Ultimately he failed to get it into production while the war was still raging, and it was only perfected by 1921. Thompson went to Britain that year to oversee the tests of his weapon by the Small Arms Committee. The tests were conducted at Enfield on the 30th of June and the SAC did not draw comparisons to the MP18, describing the Thompson as a weapon of “an entirely new type”. Regardless, the impressions were generally positive, and the gun functioned well, attracting considerable interest, although there was no serious consideration to issue such weapons to British troops at the time.

The M1921 Thompson. Designed strictly as a military and police weapon, it earned a negative reputation as a gangster’s best friend during the 1920s.

The M1923 Thompson was a failed attempt to market the Thompson in the role of a machine gun. It was tested by the British and French armies but rejected.

In 1928, the Thompson was tested again at Enfield. This model was a British-made version that was the result of a combined business venture between Birmingham Small Arms and Thompson’s Auto Ordnance Company. Their goal was to arouse European (although primarily British) military interest in the Thompson. The BSA-made Thompson had rifle-like ergonomics but was basically the same gun as the Thompson M1921, but offered in a variety of calibers, including the standard .45 ACP, 9mm Bayard, 7.63mm Mauser, and 9x19mm Parabellum. The model tested by the SAC at Enfield was fitted with a Cutts compensator, which would become standard on the M1928 Thompsons, although the SAC was of the opinion that the compensator made virtually no difference to the weapon’s performance. The BSA Thompson was not investigated any further.

The same year, the Revelli automatic rifle - a single-barreled version of the Villar Perosa developed in Italy shortly after the war - was tested, again at Enfield, by the designer himself. There was little interest from the SAC.

The British-made M1926 Thompson. By all accounts a perfectly good weapon that should have been a success, but was hindered by conservative attitudes.

The Revelli, often called the “OVP” after its place of manufacture, was designed in 1920 and was used by the Italians in North Africa during WWII.

The Vollmer was tested in 1932 and the Solothurn S1-100, designed by German engineers but manufactured in Switzerland and Austria to evade the conditions of the Versailles Treaty, was tested at the end of 1934. Both guns were compared to the MP18 but failed to impress. On the 29th of September 1936, the Finnish Suomi was tested. The gun was expensive, at £31, but was considered by the SAC to be the “best “gangster” weapon we have seen”. This was the first use of the term “gangster gun” by the British authorities in regards to submachine guns, no doubt in reference to the notoriety that the Thompson gun had picked up in the US during the prohibition era.

The Solothurn S1-100 was an immaculately-made but very expensive submachine gun. It was adopted by Austria as the MP34 in 1934.

The Finnish Suomi gun was one of the better submachine guns on the market before the war. It performed very well during the brief Winter War of 1939.

1937 saw two submachine guns tested by the SAC. The first was the American .45 Hyde, demonstrated on the 23rd of June. It was fitted with a double magazine consisting of two interconnected magazines fixed side-by-side. The SAC liked this novel feature but paid less attention to the gun itself. In December of that year, the SAC tested what they described as a Spanish Star machine carbine, chambered in .32 caliber. I am actually unsure what this weapon might have been, since there were few Spanish submachine guns at that time and those that did exist were all chambered in 9mm Largo, but I assume it was a rechambered Star Si35. Regardless, the SAC held a low opinion of it.

The Hyde, chambered in .45 ACP. Considered a rival to the Thompson, it lost out to that weapon in both British and American trials.

An experimental .22-calibre Hyde demonstrated at RSAF Enfield in the 1930s.

In 1938, several weapons were brought to the attention of the SAC. They were the Japanese Nambu submachine gun, the Danish Brøndby, and the Finnish Suomi.

The Nambu gun, known simply as the Type 1, was of interest because of its small build and light weight. It was considered a decent weapon for vehicle crews - what we would now call a personal defence weapon or PDW. The Nambu was rejected for two reasons: its 8mm chambering, since the Japanese 8mm cartridge was not readily available in Britain nor was it considered powerful enough for British use; and its long, 50-round curved magazine, which was ergonomically awkward and made the overall height of the weapon over 11 inches.

The Japanese Nambu submachine gun was one of the first submachine guns to feed through the pistol grip, although it was too bizarre for it’s own good.

The Brøndby submachine gun was sent as part of a series of gas-operated weapons designed by Fridtjof Brøndby, including a rifle and light machine gun. They were tested in March 1938. The submachine gun was chambered in 7.63mm Mauser and fed from a small 15-round magazine. This wouldn’t have been so much of a problem if the fire rate was not as high as it was: 818 rounds per minute. The SAC gave the Brøndby a positive write-up and arranged trials to compare it to other existing submachine guns, including the German S1-100 and MP28, the American Hyde, and the Finnish Suomi. However, interested lapsed and the trials ended up not taking place at all.

The Danish Brøndby was an early gas-operated submachine gun that failed to attract any buyers, despite showing promise.

In the August of 1938, the SAC received the first British-designed submachine gun, the 9x19mm Biwarip. It was an unusual little gun, largely unlike any the SAC had encountered before. It had no stock or sights and was extremely light and compact; the overall handling felt more like that of a machine pistol than a submachine gun. The SAC decided it was uncontrollable in automatic fire and took no further action with it.

At the end of the year the SAC tested an Estonian Suomi with a 50-round dual magazine, similar to the Hyde gun described earlier. The SAC liked the idea so much that they asked RSAF Enfield to consider copying the concept and applying it to Bren guns, which, as far as I know, was never actually done. The Suomi gun itself was once again shot down by the General Staff, who unequivocally reiterated that no such weapon would be adopted by the Army.

The Biwarip was the first British submachine gun. It wasn’t great, but it served as the basis for the Sten and later the Sterling.

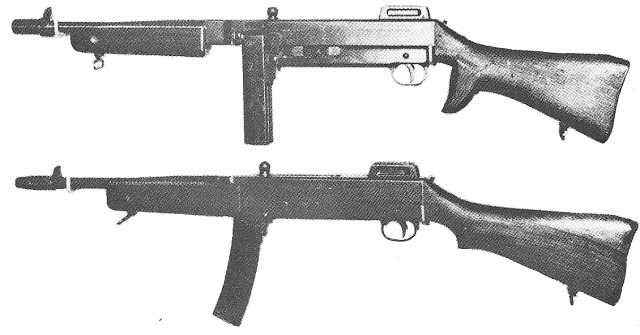

In 1939 the SAC was replaced by the Board of Ordnance, which only investigated two submachine guns that year. They were the BSA-Kiraly and the Erma MP38. The Kiraly design was submitted to the SAC via Mark Dinely, who himself had designed an experimental .32 submachine gun. Dinely’s firm, Dinely & Dowding, imported blueprints of a new design from Hungarian engineer Pal de Kiraly. The Ordnance Board were interested and ordered a batch of prototypes. Production rights were given to Birmingham Small Arms, who produced a small quantity at the low cost of £5 per unit.

The prototypes were submitted to Ordnance Board in May. The guns had some novel features, like pivoted magazine housing that could fold under the barrel. Firing tests were positive and there were no major reliability or performance issues recorded. The Ordnance Board was not as impressed by the almost indescribably complex trigger mechanism, which used a flywheel, tape, and spring mechanism to moderate the rate of fire. Kiraly offered to simplify the mechanism to make it easier to manufacture, but the Ordnance Board never showed any further interest, which was perhaps a huge mistake - at such a low cost, thousands of these quality submachine guns could have been produced by BSA and issued to British troops before the war had started. Ultimately, though, it was not to be.

The BSA-Kiraly prototype. An excellent weapon that unfortunately didn’t get very far. The design evolved into the Hungarian Danuvia submachine gun.

The last submachine gun investigated by the Ordnance Board in 1938 was also in May. It was the Erma MP38, the new German submachine gun, recommended to the Ordnance Board by the Director of Artillery. He was alarmed by the extremely fast production of this weapon in Germany and asked the Ordnance Board to consider such a weapon, especially now that war was looming. Tests were conducted and the MP38 was found to be a quality weapon but no action was taken. Even if there was any major interest in the design, the mounting tension between Britain and Germany would have made adoption of the MP38 impossible. Interestingly, in 1940, the Royal Air Force ordered 10,000 British-made copies of the MP38, a request that was shelved in favor of the Lanchester.

War finally broke out on the 2nd of September 1939. When the British Expeditionary Force were sent to France later that year, they filed a request to the Ordnance Board asking for an immediate supply of submachine guns. Several guns were sent for trials in France, conducted by the BEF. Not all the weapons tested were actually submachine guns; some were rifles and light machine guns modified to fill a similar role.

The submachine guns tested were the American Thompson and Hyde guns, the German-designed Solothurn S1-100, and the Finnish Suomi. The American Johnson rifle, the Czech ZH-29, and the French RSC were converted into automatic rifles and also tested. Modified Lewis and Bren guns were also tested in the role of a hip-fired submachine gun.

The Solely gun, a modified Lewis that was briefly considered as a stand-in for a true submachine gun. It used Bren magazines.

Unsurprisingly, the Thompson was favored. The British Army hurriedly pressed Thompson guns into service, but it was too little, too late. By the time fighting broke out in May 1940, the majority of British soldiers found themselves without a submachine gun and the Germans had plenty. After the disastrous “Fall of France”, the British evacuated from Dunkirk and found themselves in a precarious position, faced with potential invasion. British small arms philosophy was made completely redundant by German tactics and the Army was forced to reconsider its approach to submachine guns completely.