British experimental machine guns

During the first half of the 20th century, the bulk of Britain’s machine gun arsenal was made by Vickers. The Vickers Mk.I, based on the Maxim gun, entered British service in 1912 and was used throughout World War I. Afterward, there were constant attempts to improve it or modify it to fill different roles. Most were chambered in the standard British Army cartridge, .303 calibre.

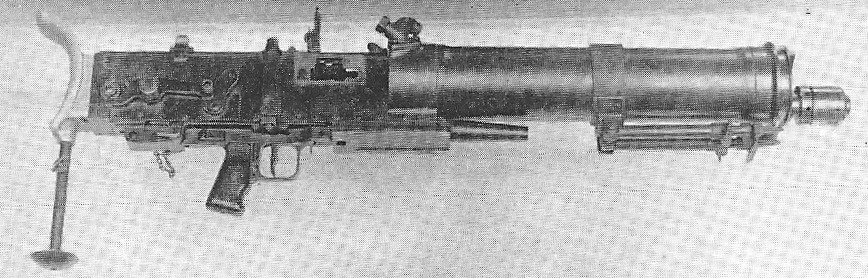

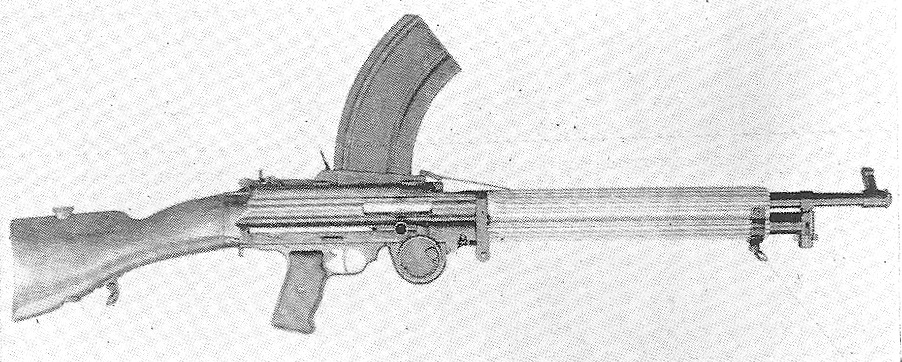

Many experimental Vickers guns were made for Armored Fighting Vehicles (AFVs), and were all derived from the basic Vickers Mk.I but usually had dovetail mounting plates. The Mk.IV, Mk.V, and Mk.VI prototypes were all similar variations on this premise. The Mk.VII was an ambitious dual-role machine gun that could be used as an AFV gun or an infantry machine gun, however it was considered too impractical as the latter.

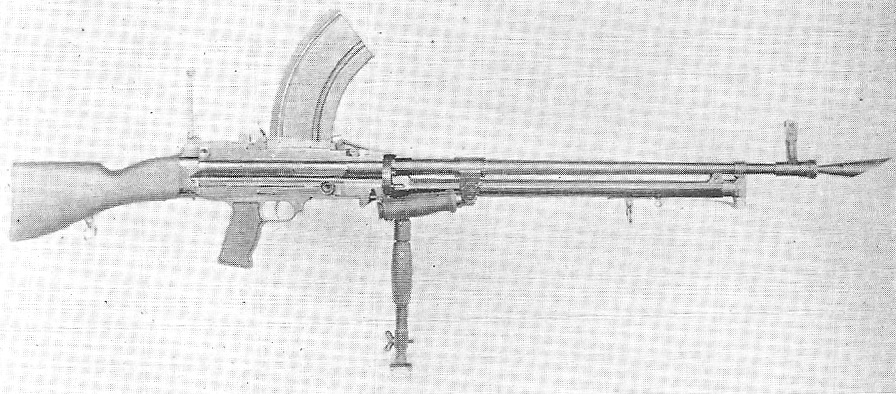

After the Mk.VII, Vickers developed a smaller-calibre AFV gun with an air-cooled barrel covered by an aluminium shroud. It was, unusually, selective-fire. It was designed as an anti-infantry weapon and was useless against armor - probably the reason it wasn’t successful.

image

The Vickers Mk.VII, an attempt to create a two-in-one machine gun. It had an in-built vehicle cooling system.

image

The Vickers Class A, a smaller-calibre AFV gun. It had a second trigger for single-fire, a feature scarcely needed for machine guns.

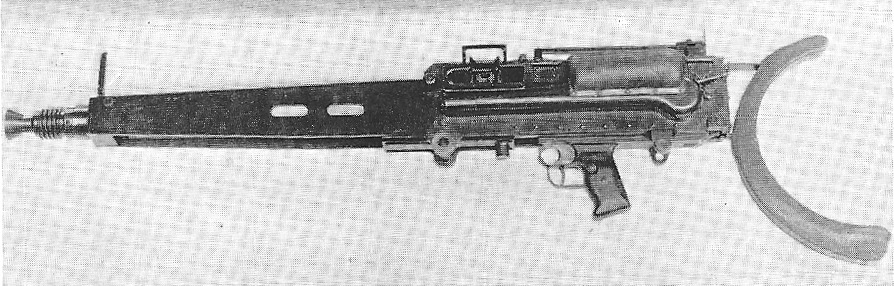

Vickers began producing prototypes in the more powerful .5 cartridge to satisfy the Army. The .5 Mk.II was accepted into service in 1933, followed by the Mk.III, which was used as an anti-aircraft gun by the Navy. The improved Mk.IV and Mk.V models were designed for tanks but were not taken into service.

Vickers were also approached by a group of investors to produce prototypes of a strange twin-barreled machine gun. It was gas-operated and alternated between barrels to prevent overheating. The project failed to arouse any commercial interest, however, and was dropped relatively quickly.

image

A prototype Vickers Mk.I in .5 calibre. The lack of a muzzle brake meant recoil was very strong. The improved version, the Mk.II, was accepted into service.

The Vickers twin-barrel prototype. It was funded by private investors but failed to find any buyers.

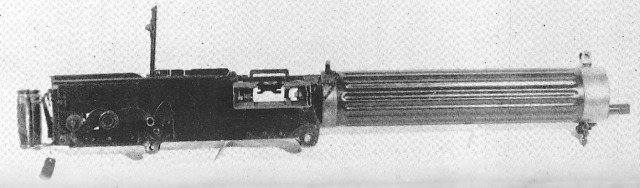

In 1924, Birmingham Small Arms marketed their new .5-inch (what we would now call .50 caliber) machine gun, intended to be used as an observer’s gun on planes or an anti-aircraft gun on ships. Despite bearing a heavy resemblance to the Lewis gun, it was recoil-operated. The barrel and carrier recoiled back and the carrier would be stopped while the barrel would return on its own. The carrier would not return until the empty casing fell out. When all the ammunition was expended, the barrel and carrier would not return at all and would stay recoiled until a new round was chambered. The fire rate was a mere 400 rounds per minute and the magazine held only 37 rounds. The gun was tested by the RAF in 1928 but rejected.

In the 1930s, BSA tried again with the Adams-Wilmot aircraft machine gun, chambered in .303. This one was gas-operated and fed from 90-round pan magazines. The gun was entered into RAF trials in 1934 but proved so unreliable that it was disqualified early on. The trials proved of little consequence anyway since observer’s guns became obsolete shortly afterward, replaced by powered aircraft guns.

The BSA .5 machine gun. It looked like an oversized Lewis gun but was internally nothing alike, and did not attract any customers.

The BSA Adams-Wilmot. The firing pin was extremely fragile and the feed system was prone to failure. The gun broke during testing.

When World War II broke out in 1939, Britain was using the Bren gun but feared that long-term production of it would prove too expensive. Harry Faulkner of BSA came up with a solution in the form of the BESAL machine gun. The BESAL was made in two models: a Mk.I, which was basically a simplified Bren, and a Mk.II, which was a slightly more sophisticated gun based on the Czech Zb.60. It cocked by pushing forward and then pulling back the pistol grip. The BESAL was designed to be very cost-efficient and could be produced en masse in the event that RSAF Enfield was ever bombed by the Germans and production of the Bren was sabotaged. Fortunately for the British Army but unfortunately for BSA, this never happened, and thus there was no requirement for the BESAL.

The BESAL’s nomenclature was the source of some confusion when the BESA machine gun came into service, so the name was changed to simply the Faulkner machine gun. BESA stood for Brno, Enfield, and BSA.

The BESAL Mk.I. This version was cocked conventionally by a handle on the right side of the receiver. Basically a Bren stripped down to the bare essentials.

The BESAL Mk.II, or Faulkner. A decent gun, the need for which never arose.

The BESAL’s bolt, return spring and piston, showcasing the lack of complexity.

Earlier in the war, the Army investigated a .303-calibre machine gun developed by the Soley Arms Company. The Soley machine gun was a modified Lewis, converted to feed from Bren gun magazines. The overall length was shortened and the weight lightened. Although a gun of this type would have been decent in the role of a squad support weapon, it was actually intended to be used as a placeholder for a submachine gun, which Britain did not have at the time. Limited numbers of Soley guns were sent, among a hotch-potch of other SMGs and auto-rifles, to the British Expeditionary Force in France. The guns were field tested but not pressed into service.

The Soley Arms Company had a bit of a reputation. In the late 1930s they sold hundreds of obsolete weapons at massively inflated prices to the Spanish Republic during the civil war there. The founder of the company was a former RFC officer who was, by all accounts, a roguish fellow. He came under much scrutiny in the US when he was brought up before a committee that investigated corruption in the arms trade.

In 1941, Rolls-Royce developed a .5 aircraft gun and submitted it to the Board of Ordnance for testing. It was recoil-operated and used projecting locking lugs. Initial trials took place at Pendine and it performed well enough but feedback from the tests recommended that Rolls-Royce develop a .55-caliber version. When the new .55 model was tested, it did not perform as well. The project was then vetoed by the Ministry of Aircraft Production.

The Soley-made shortened Lewis. It was tested by the bemused BEF in the role of a submachine gun. It fed from .303 Bren magazines.

The Soley Mk.IV. This was made for similar reasons to the BESAL. The Soley Arms Co. could’ve converted thousands of Lewis guns but were declined.

The Rolls-Royce aircraft gun. It showed some promise but suffice to say, it was not the “Rolls-Royce of machine guns”. The build quality was excellent.

After the war, the British Army sought new weapons in pretty much every field and RSAF Enfield, being the largest state-owned small arms factory in Britain, was obliged to meet these demands. They developed experimental weapons of every kind, although few ended up actually being adopted.

One of the experimental weapons developed at Enfield was a .5-inch machine gun designed by Russel Shepherd Robinson, an Australian engineer who had initially come to the UK to demonstrate an interesting machine pistol, but was now working at Enfield. Robinson’s machine gun used a sliding block mechanism and had a very complex extractor that pushed the casings outward under the barrel. It was much too complicated to be used by the Army and Enfield cut the funding for the project after a series of short tests.

With the failure of the project, Robinson emigrated to America and worked on experimental machine guns for the US Army. His Enfield prototype evolved into the M73 machine gun, which was mounted on M60 Patton tanks, and wasn’t particularly reliable.

The Robinson .5 recoil-operated machine gun. It was designed for tanks but would have been too expensive to produce in significant quantities.

Enfield allocated most of their engineers towards the Experimental Model projects, which encompassed rifles, machine guns and submachine guns. The first of these guns to be completed was the EM-1, designed by a Polish émigré, Roman Korsak. It was based on the FG-42 action and chambered in a German cartridge, 7.92x57mm. Enfield arranged mock trials of the EM-1 against the EM-2 developed by Jeziorański and the EM-3 by Metcalf. They concluded that none of the guns were suitable for military trials and the decision was made to restart the whole project. Korsak was replaced by Stefan Janson, who developed the new .280 EM-2 rifle, which Enfield favored.

The TADEN was developed alongside Janson’s EM-2 rifle. Designed by Harold Turpin, the name was an abbreviation of Turpin Armament Development, Enfield. It was chambered for the new .280 intermediate cartridge and the action was derived from the Bren. The TADEN was designed to fill the role of a general purpose machine gun and it was well on its way to being adopted by the British Army, when in 1952 the newly-elected Churchill government dropped the .280 cartridge in favor of the NATO-standardized 7.62x51mm round. Thus development of the EM-2 rifle and TADEN gun came to a sudden end.

The EM-1, designed by Korsak. Basically a bullpup FG-42. Enfield didn’t think it was up to scratch and canned the project.

The TADEN. Very nearly adopted alongside the EM-2. It was scrapped but served as the basis for Enfield’s X11 machine guns.

With the adoption of 7.62x51mm, the Army began arranging trials for a new general purpose machine gun chambered in that cartridge. Enfield’s entrant was the X11 GPMG. Based on the same principles as the TADEN, the X11 was a modified Bren re-chambered for 7.62 and feeding from a belt. The belt was operated by a piston which caused a lot of friction interference and therefore stoppages. Four different prototypes were made but the problem was never fully remedied. The barrel, on the other hand, was excellent and the X11 was possibly the most accurate and precise GPMG on offer at the time.

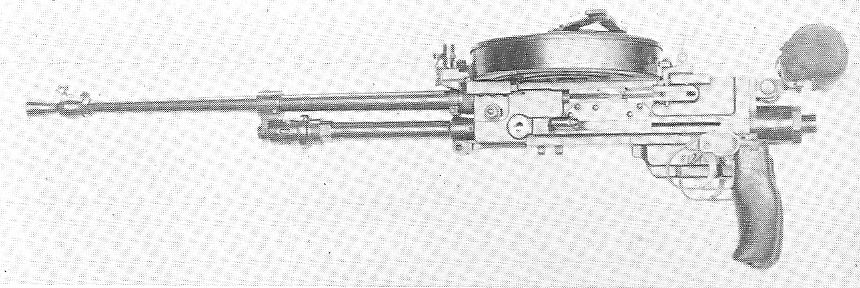

BSA, meanwhile, had their own entrant known in trials as the X16. Again, this was based on the Bren and utilized belt-feed from the right-hand side of the receiver. The X16 was built to a higher standard than the X11 and had a very smooth action. The feed shaft was operated by a gas piston and was particularly reliable. Ultimately, though, it was too expensive to produce in large numbers.

The BSA GPMG. It was what it looked like, a 7.62mm Bren. It could be fed from a belt or a drum magazine.

The Enfield X11E4. Extremely accurate but not as reliable as the BSA gun.

The entrants into the troop trials in 1958 were the Enfield X11, the BSA X16, the American M60, the Danish Madsen-Saetter, the French AA52, the Swiss MG50 and the Belgian FN MAG. The MAG was considered the best gun and was adopted as the L7A1 GPMG, and is still in service today.